Why the stock market doesn’t like high inflation

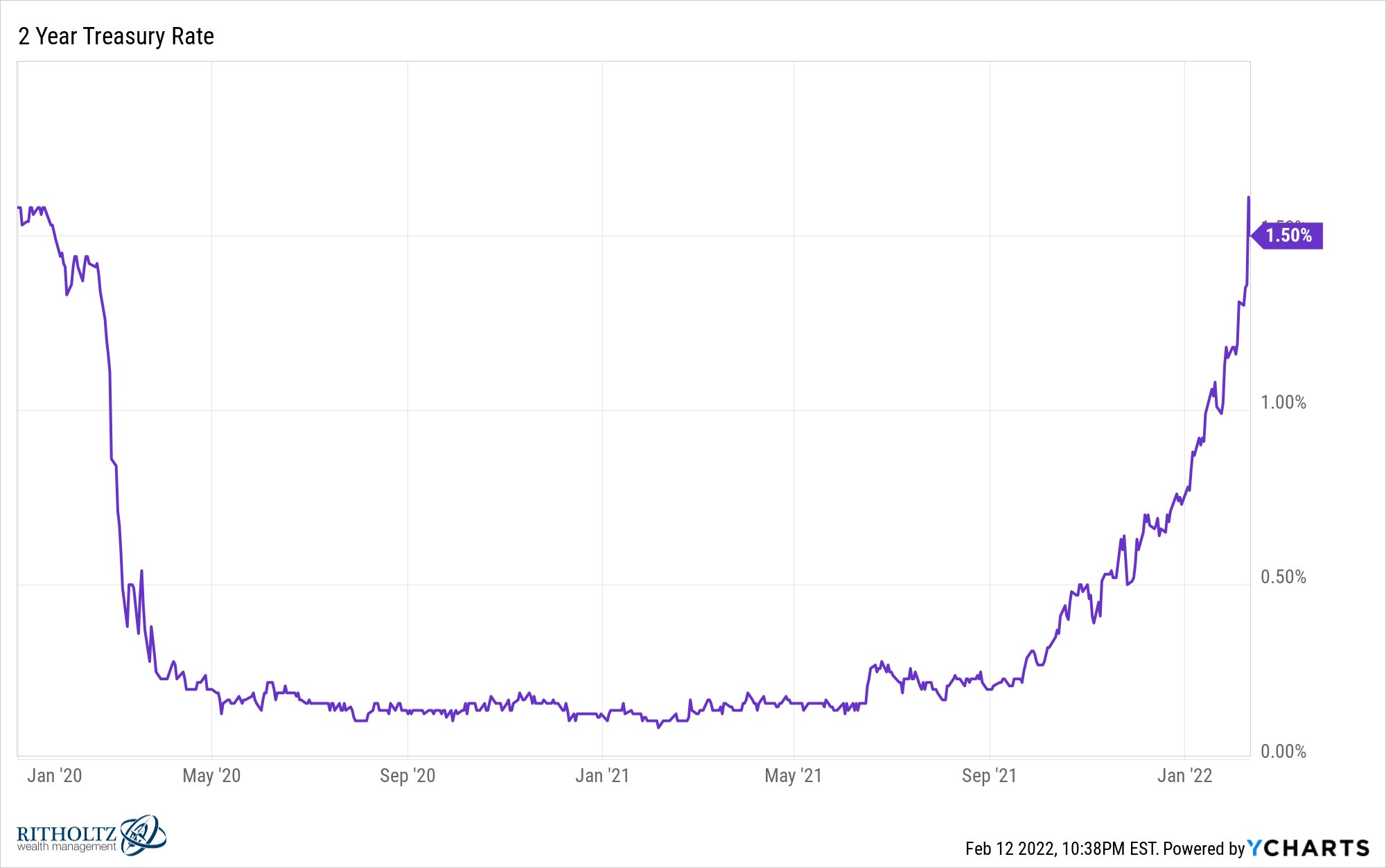

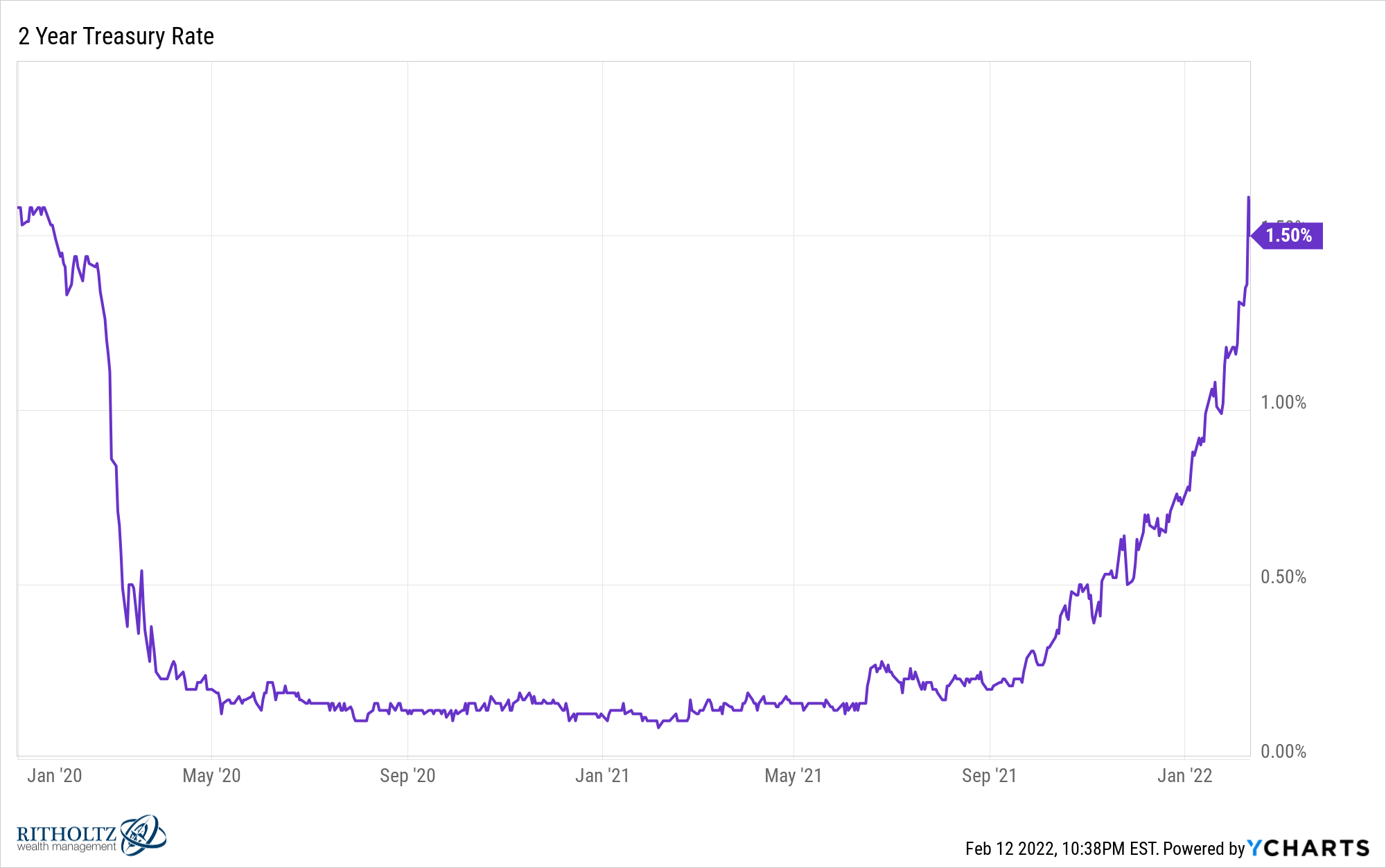

There are two ways to look at the following chart of short-term bond yields:

In one way, it is a crazy move to delay short-term government bond yields. The pace at which we are seeing a revaluation of bond yields based on inflation data and the prospect of a Fed rate hike is breathtaking.

Look at the pattern of that smile since the start of the pandemic.

Another way to look at this chart is that the two-year Treasury yield ended 2019 at 1.6%. After a flurry of both fiscal and monetary stimulus due to the pandemic, the two-year Treasury yield is once again around 1.6%, despite a much higher inflation rate than we saw at the end of 2019 (2.3%).

The two-year Treasury yield has risen from a low of 0.09% (9 basis points in finance) to the current level of 1.5% in a matter of months.

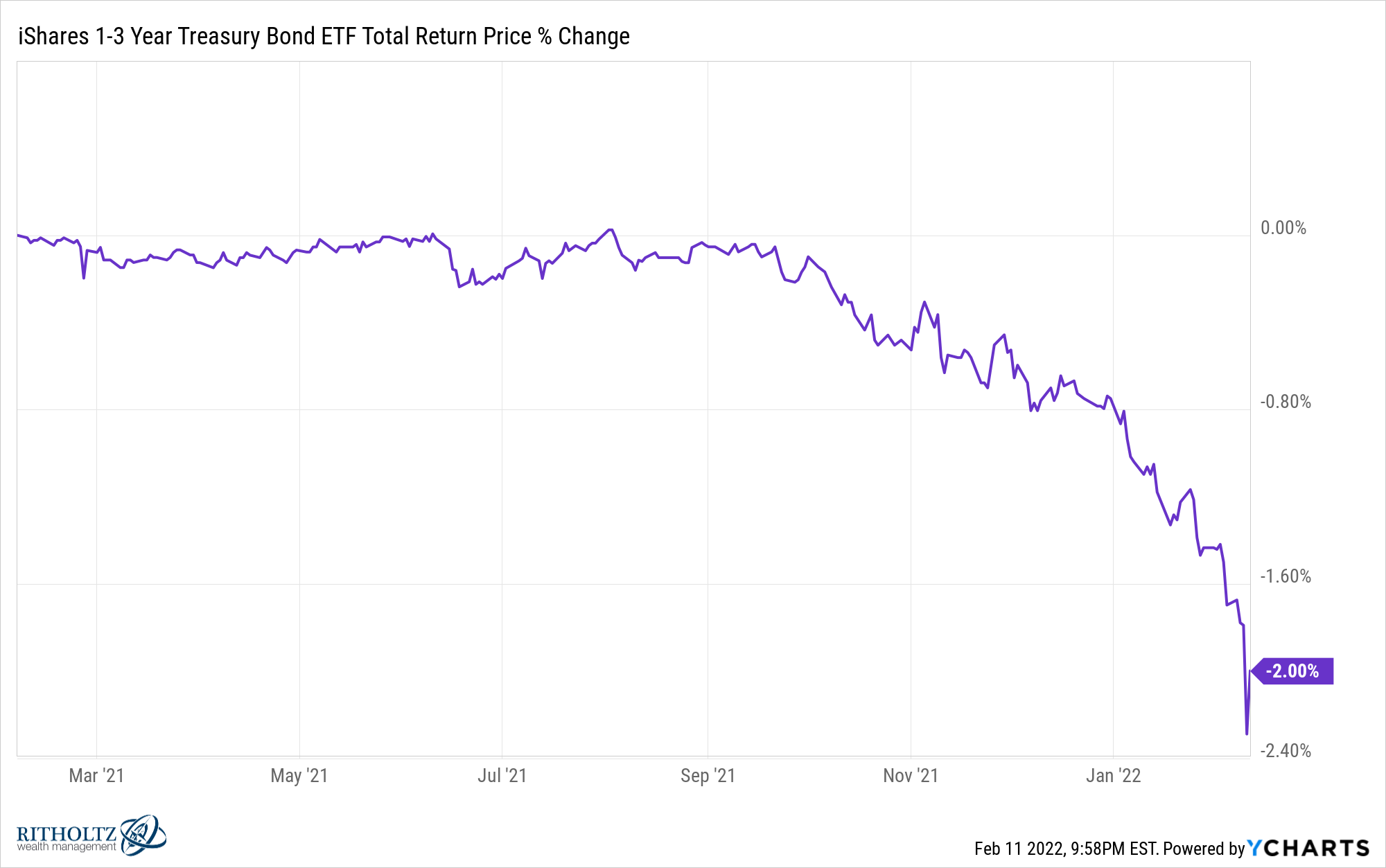

Surely this rise in rates has crushed short-term treasuries?

How can they not be crushed when rates have gone up 17 times over the past year or so?

Bond prices and bond yields are inversely related, so when yields rise, prices fall and vice versa.

Here are the total returns for the iShares 1-3 Year Treasury ETF (SHY) from the two-year rates below as of early February 2021:

Wait a minute – this can’t be right. How is it possible for rates to rise 17 times in one year, but with short-term bonds losing only 2% of their value?1

Granted, losing money when investing in short-term bonds isn’t fun, but a 2% loss is a bad time in the stock market. It’s just a flesh wound.

It’s important to remember that it’s not rising interest rates, it’s bad for bonds — it’s inflation. While the SHY is down 2% on a nominal basis over the previous year, it is down around 10% on a 7.5% inflation rate.

Inflation poses a much greater risk for leaps than rising rates.

Those higher rates eventually translate into higher returns for your bond holdings. But inflation eats away at the purchasing power of your fixed income payments over time.

Stocks are not exactly like bonds when it comes to their risk-return profile, but they do have a similar relationship when it comes to rates and inflation.

The stock market actually holds up quite well in a rising interest rate environment (see here).

The stock market does not perform well when inflation is rising (see also here).

The stock market is still one of your best bets for hedging against inflation over the long term, but the continued movement of higher prices can dent stocks in the short-to-intermediate term, especially on a real basis.

Warren Buffett wrote about this in the 1970s, which was the last time the United States experienced above-average inflation for an extended period.

Buffett wrote How inflation deceives equity investors in 1977.

The annual inflation rate that year was operating at around 7%. The average inflation rate over the last 7 years was also close to 7%, up from 11% in 1974. It will average closer to 11% per annum over the next four years.

Buffett’s main takeaway is that stocks are more akin to bonds than most investors, especially when it comes to investing in an environment of extreme inflation:

I believe the main reason is that stocks, financially, are virtually identical to bonds.

I know this belief will seem singular to many investors. They will immediately see that the return on bonds (coupons) is fixed, while the return on equity investments (earnings of the company) can vary greatly from one year to another. true enough. But anyone who examines the total returns earned by companies during the post-war years will discover something extraordinary: Return on equity doesn’t really vary much.

Buffett’s argument here was based on the idea that the return on equity for American corporations is relatively stable over time at around 12%. ROE measures how much profit a corporation makes for every $1 of shareholder equity.

Obviously, what people are willing to pay for ROE can vary quite violently at times, but ROE itself is relatively sticky.

Using this framework you can think of shares as a perpetual bond that never becomes payable.

If the ROE on stocks does not change that much, high inflation would be detrimental because investors would receive a smaller share of the profits to compensate for the higher cost of living.

Buffett explains:

Even if you agree that the 12% equity coupon is more or less irreversible, you can still expect to do well with it for years to come. It is conceivable that you would. After all, a lot of investors did well with it over the long run. But your future results will be governed by three variables: the relationship between book value and market value, the tax rate, and the inflation rate.

So we are: 12% before taxes and inflation; 7% after tax and before inflation; And probably zero percent after taxes and inflation. It hardly seems like a formula that stamps all those cattle on TV.

You will have more dollars as a common shareholder, but you may not have as much purchasing power.

Unfortunately, that means higher inflation could be bad for both stocks. And Jump.

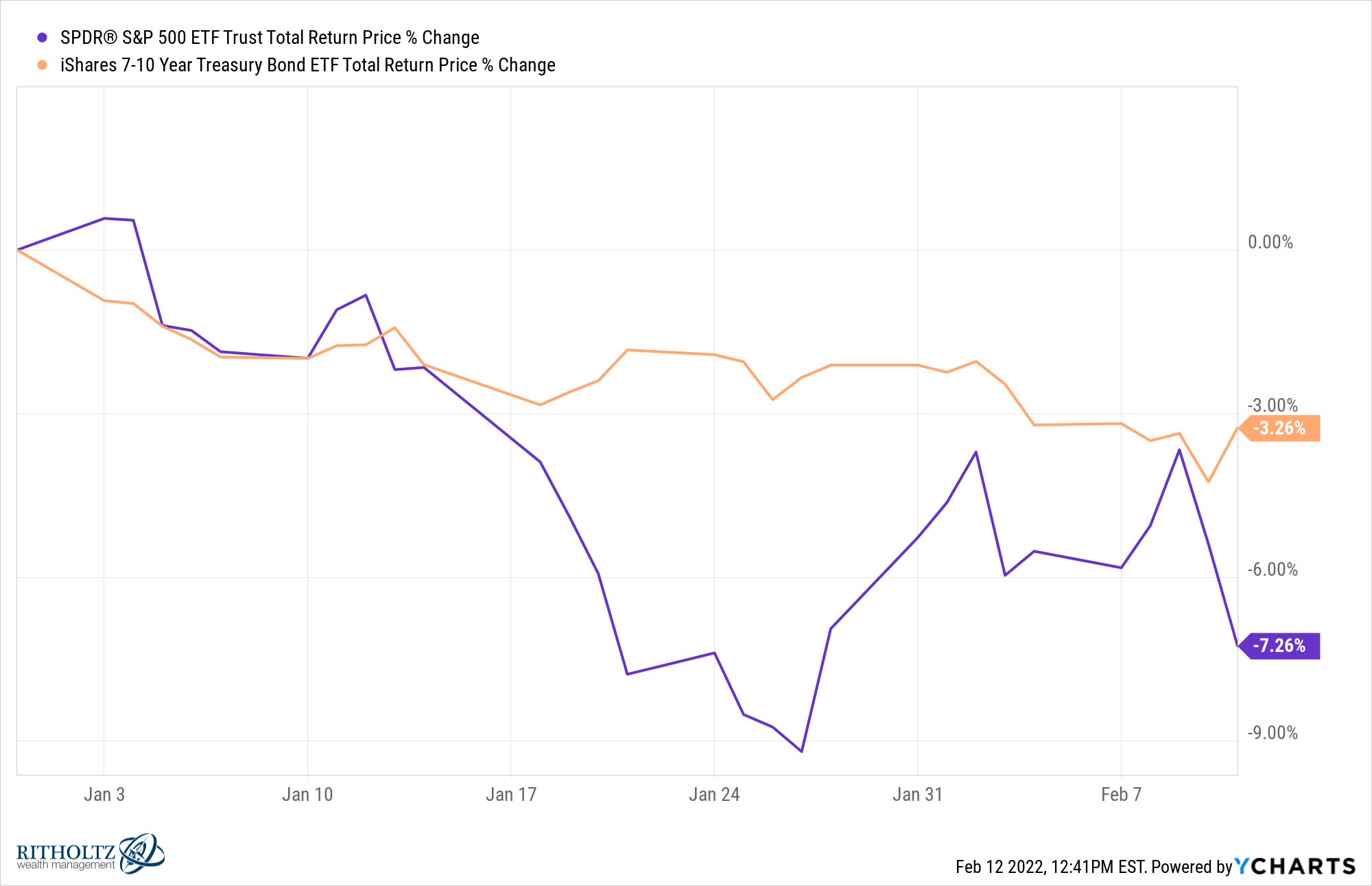

Interestingly enough, even on a modest basis the year is off to a poor start for both stocks and bonds:

We’re only 6 weeks into the year, so it’s a bit premature to draw any firm conclusions, but if it were to hold then both stocks and bonds have ended the year in negative territory.

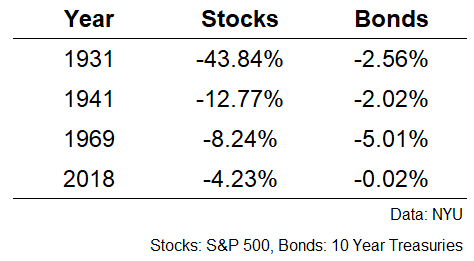

I found only four examples in the last 90+ years of data where both stocks and bonds fell in the same year in the US markets:

We find ourselves in an awkward economic situation this year with high inflation and rates rising from low levels, the perfect environment for this to happen.

Two of these four examples include years with above-average inflation (it was above 5% in both 1941 and 1969).

The questions investors need to ask themselves are the following:

does it really matter?

Does the prospect of a heavy year mean you should abandon traditional diversification?

Should you change your portfolio in the face of inflation?

What if high inflation doesn’t stick around?

I’ll offer a few ideas on how diversification across certain asset classes can help during an inflationary environment in a follow-up section.

Further reading:

How do stocks perform when the Fed raises rates?

1For comparison purposes, long-term bonds (TLTs) are down more than 10%. Short-term bonds tend to hold up better during rising rate environments, while offering lower returns.