The difference between a portfolio and a plan

A reader asks:

I have a question for all those people who have made a respectable profit in cryptocurrencies. I got into crypto during the covid crash and have made some big gains since then. Some of my trades were bitcoin at $8500, ethereum at $1300, solana at $70, etc. However, I started with 10% portfolio allocation for cryptocurrencies which increased to 20% and it did not change. Then it went from 20% to 30% and I made it back to 20%. Then it went up to 30%, then to 40%, now it’s 50% of my portfolio. Should I stick to my plan and cut my allocation or let the winners run and only allot in stocks/bonds from there?

I’m pretty sure this question came before the current crypto route. Yet with Bitcoin (-45%), Ethereum (-45%) and Solona (-60%) all in the midst of major declines, this investor is still in the black based on those entry prices.

So maybe this guy is changing his tune. But changing your tune based on how high or low the prices are is not a sustainable investment strategy.

There’s nothing wrong with changing plans when your circumstances or facts change.

Investment policies are not written in stone.

But if you do not have a disciplined policy to follow then it becomes very easy to make a mistake.

I wrote about the process of rebalancing in my book in the context of weight gain in prison:

Complaining about the food served in county jails is a favorite pastime of inmates. So it was somewhat shocking to a prison guard at a Midwestern country prison when he found that inmates serving prison sentences of six months or more were gaining an average of 20 to 25 pounds while behind bars. Once that was discovered, he sought answers from a team of researchers. The prisoners had access to the exercise yard, so this was not a problem. When asked, none of them blamed the lack of food, accommodation or exercise. If you can believe it, the reason for this actually had more to do with prison clothes. The orange jumpsuits that serve as the prison uniforms are too baggy. They were so loose on the prisoners that it was difficult for them to tell that they were gaining weight slowly because they did not have their normal-fitting clothing to indicate that they were gaining weight rapidly. There was no safety net to tell them this was happening. Once he tried to fit back into his normal clothes after jail time, he finally realized how much he had gained weight. Without clothing that would fit to give them some sort of measurement and benchmark to keep their weight under control, prisoners were adding pounds that went unnoticed.

Rebalancing helps keep your portfolio from becoming overweight (get it?).

Let’s look at a simple example. Let’s say you built a 60/40 portfolio of US stocks and bonds 10 years ago. If you had left that portfolio alone, it would now be closer to 85% stocks and 15% bonds.

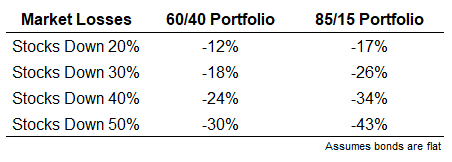

Let us now look at the potential pitfalls of these allocations during different levels of stock market downturns:

That may not seem like a huge difference, but let’s say you retire with a $1 million portfolio. In a 40% market crash scenario, this is an additional loss of $100,000. That’s real money.

Of course, the flip side of this equation is that your profits are going to be huge during a bull market when you just let your winners ride. That’s how you got 85% stock allocation in the first place.

So I think you have to ask yourself the following:

- Is this a portfolio or a plan?

- Why did I create asset allocation in the first place?

A portfolio is a set of investments thrown together without rhyme or reason. It’s the Golden Coral buffet where you take a little bit of it, uh, it looks good and you end up with a mish-mash of holdings.

A plan involves building a portfolio that balances your risk profile and time horizon. This includes probabilities, assumptions and scenario analysis. An investment plan is an ongoing process that sometimes includes course improvements.

The beauty of creating guidelines within building a plan is that you don’t have to ask yourself what to do every time one of your holdings goes too high or low.

If your plan says you sell crypto every time it reaches an upper limit of 20% (or 30% or 40% or whatever), then you sell. If your plan says you buy crypto every time it crashes and hits a lower limit of 15% (or 10% or 5% or whatever) then you buy.

Does this mean that your asset allocation will allow you to completely fine-tune the market cycle?

off course not!

But this does not lead to sensibly designed asset allocation.

The late David Swensen of Yale’s Investment Office once wrote the following:

Many investors spend too much time and energy building a policy portfolio, only to allow the allocations they have established to drift with the whims of the market. Without a disciplined approach to maintaining policy goals, fiduciaries fail to achieve the desired characteristics for the institution’s portfolio.

What’s the point of creating asset allocation if you’re not going to follow it?

Listen, all investing is a form of regret reduction. When your portfolio’s risky allocation is flying high, you’ll regret not owning it much. And when your portfolio’s risky allocation is running out, you’ll regret owning more cash and bonds now.

You can always hold a focused position and never sell or rebalance around it.

You just have to be prepared to live around that focused position with the potential for a wide range of outcomes. This is great when more upside is involved in that wide range but when it is more negative it can be painful.

Successful investing requires an understanding that there are always going to be trade-offs to every decision you make.

We talked about this question on this week’s Portfolio Hedge:

I also had Chris Wayne to discuss some financial planning topics, how to cut risk when you have too many stocks, and how to treat pensions when it comes to building a portfolio.