What does the bond bear market look like?

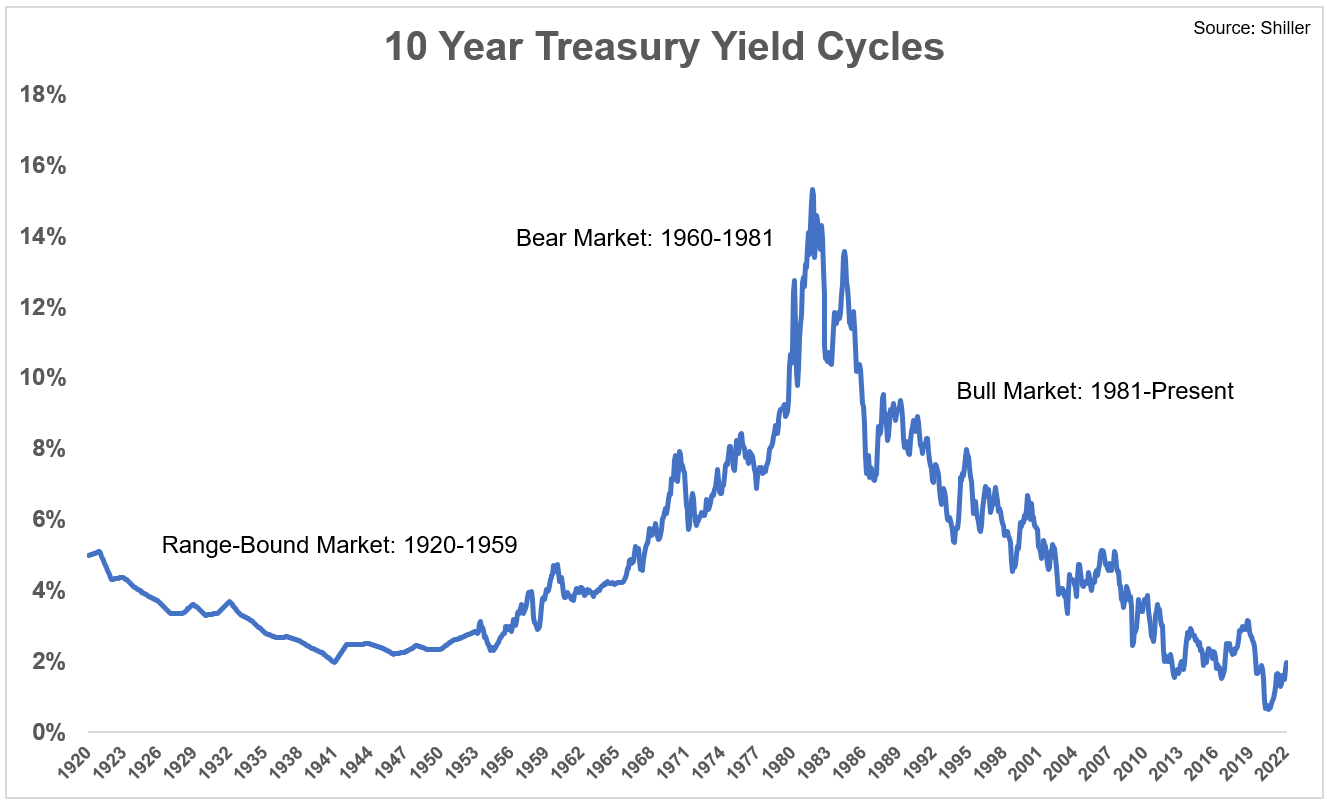

There have been basically only three long-term bond market cycles for US government bonds over the past 100 years:

The first cycle of 1920–1959 ranged interest rates from around 2% to 4%. This resulted from a combination of deflation after the Great Depression and a cap on rates in the 1940s to help with World War II.

Inflation accelerated in the 1960s and rates followed their uptrend. Prices rose even more in the 1970s and inflation did not subside until the Fed raised rates to more than 20% in the early 1980s. That bear market lasted more than 20 years.

The post-deflation period is probably the most impressive bond bull market ever and will not be repeated. There have been many spikes along the way but the trend in interest rates is below 40+ years.

They are now rising again 10 years from a low of 0.5% in the summer of 2020 to 2.5% now.

is this the end? Is the four-decade bond bull market over? Should Investors Be Prepared for a Bear Market in Bonds?

I’m not smart enough to know these answers, but I thought it would be helpful to look at what happened last time bonds were in an ever-increasing rate environment.

The first thing to understand is that a bear market in bonds is nothing like a bear market in stocks. This is because bond returns are usually guided by math whereas stock market returns are guided by emotion.

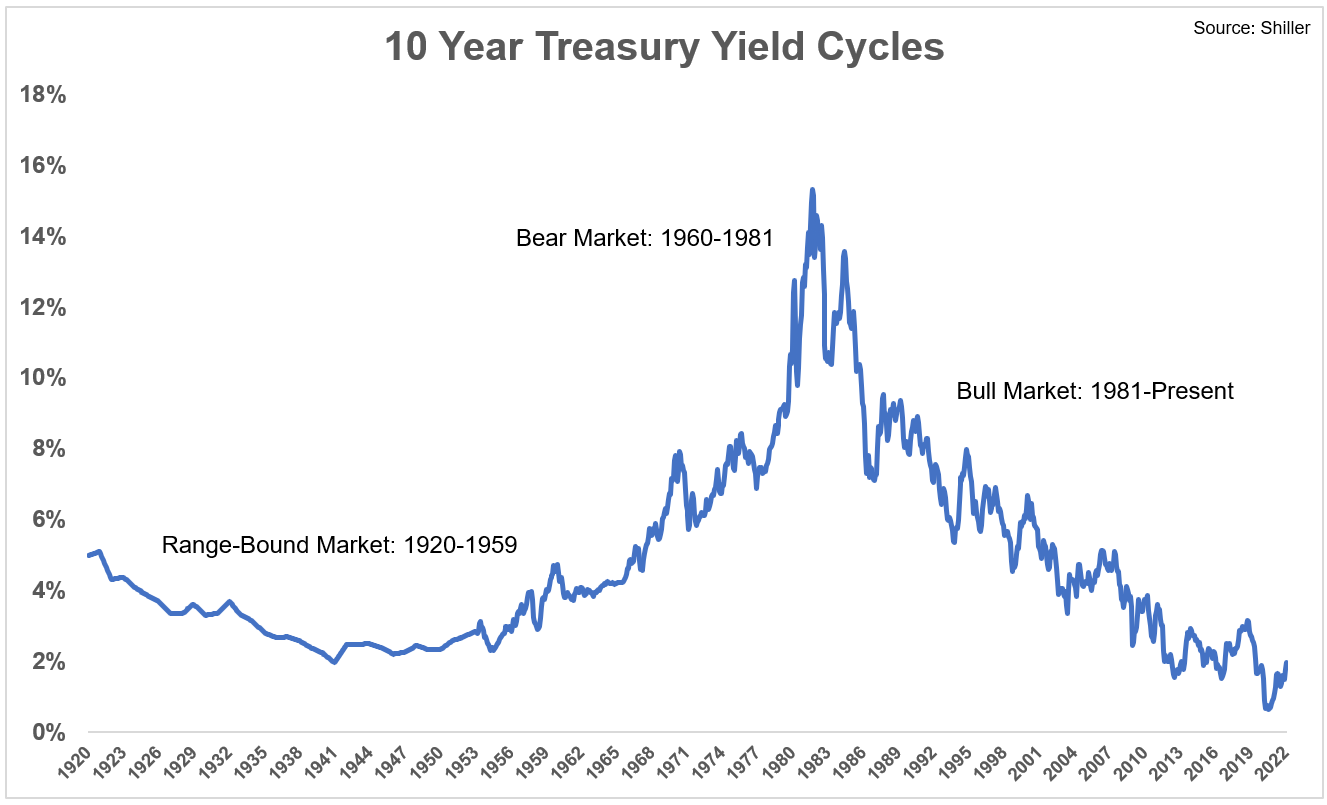

The best way to predict future returns in the bond market is to start with the current interest rate. This chart from a Fortune piece I wrote is a few years old but the relationship still holds up:

Fluctuations in interest rates can cause short-term volatility in bonds, but in the long term, the beginning of interest rate levels wins out.

The 5-year US Treasury is currently yielding 2.5%. If you invest in intermediate bonds, your returns are likely to be close to 2.5% per annum over the next 5 years.

But what about rising rates, Ben?!

Let’s walk down yield lane and look at what happened during the last bond bear market.

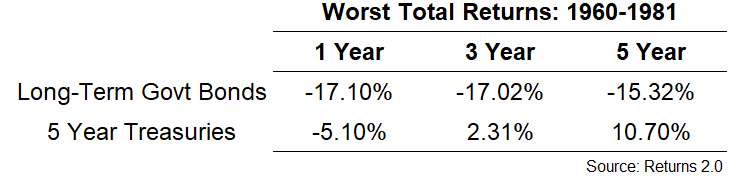

These were the annual returns from 1960-1981 for long- and intermediate-term bonds:

- Long Term Government Bonds +3.0%

- 5 Year Government Bonds +5.4%

Those returns look great for a period in which the 5-year Treasury yield rose from about 3% to over 16%.

The reason for these good nominal returns is that it took more than 20 years for the yield to climb from 3% to 16%. And finally, those rising yields helped offset some short-term price losses.

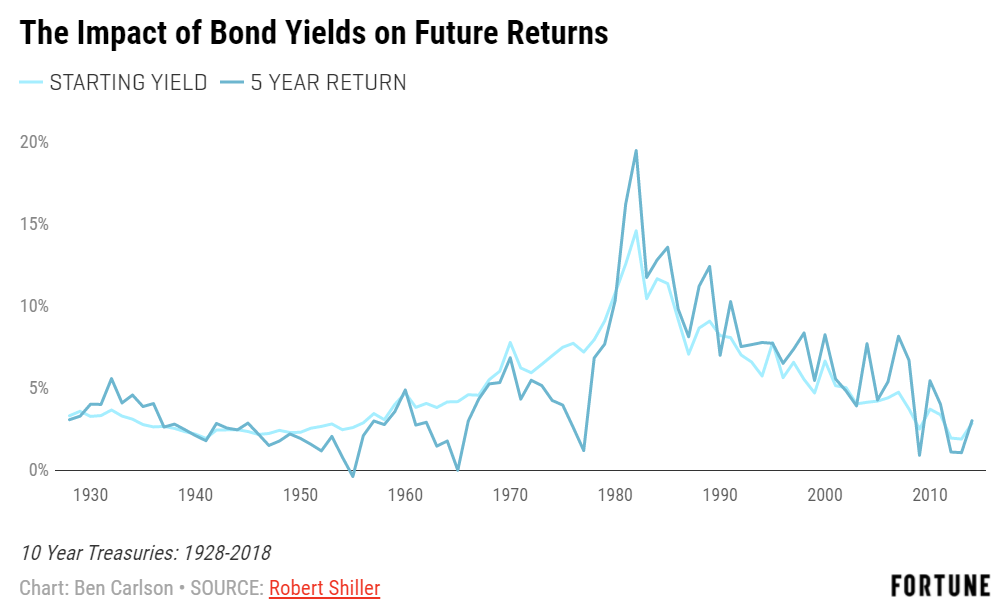

Of course, there was some downside in the short term from the massive increase in yields. These were the worst 1, 3 and 5 year total returns from 1960-1981:

The loss here doesn’t look so bad when you consider the steep rise in rates in this time frame, but longer-term bonds certainly take it on the chin.

Unfortunately, inflation was 5.3% per annum during this 22-year period. So intermediate-term government bonds got positive returns off the skin of their teeth, while longer-term government bonds were hit by inflation.

It’s worth noting, yields were growing much higher in 1960 than they were this time with rates lower. We have never seen yields drop as low as they were at the height of the pandemic market turmoil.

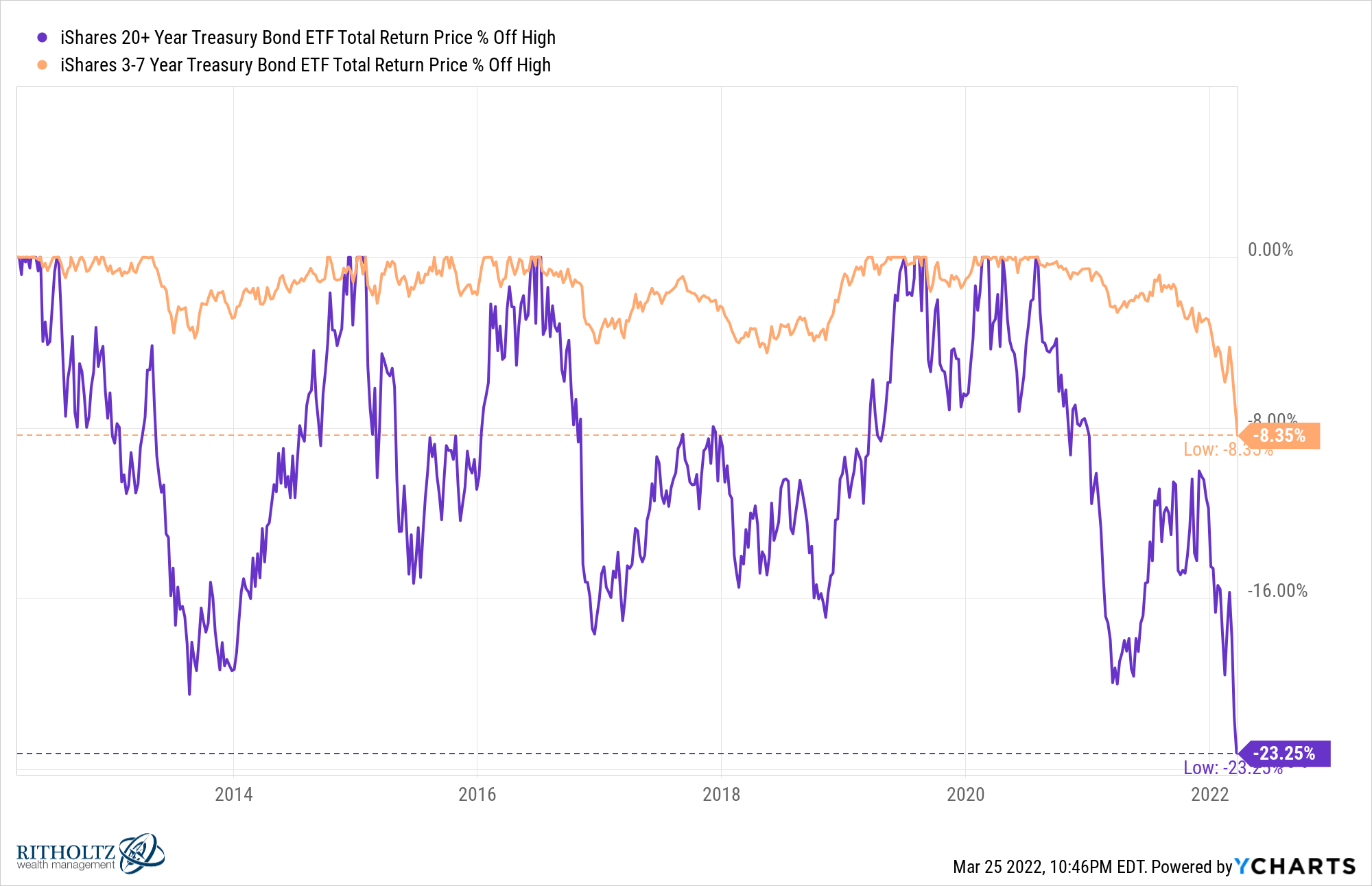

In fact, if we look at the current decline in long-term bonds, it is worse than what we saw during the bond bear market of the 1960s and 1970s:

Intermediate bonds are also in the midst of a decline of their own.

It doesn’t feel like it now, but ultimately, higher yields are a good thing.

Going into 1977, the 10-year Treasury was yielding around 7%. By the end of 1981, yields were just shy of 14%. Since there is an inverse relationship between yields and prices, bonds must have been crushed, right?

Well it wasn’t a good run for the bond, but with interest rates doubling to ridiculously high levels the returns were better than you’d think.

Interest rates rose by more than 7% over 5 years, but 10-year Treasuries were actually just over 6% (a little over 1% per year) overall at this time.

Of course, inflation was running around 10% per year over the same time frame, so the real return was seriously negative.

This is the most important point to understand about bonds – inflation is a far greater risk than rising rates.

Rising rates can sting in the short run but lead to higher returns in the long run.

The biggest risk for a fixed income investor is high inflation because it eats up your periodic cash payments over time.

I am not suggesting that we are heading for another 1960-1981 bond bear market. It is always possible but it is extremely difficult to predict the path of interest rates.

You can talk me to very, very high rates in this cycle or yield ranges for years to come.

However, it is important to understand the ongoing dynamics in a bond bear market because there isn’t much precedent for one.

U.S. government bonds don’t necessarily crash like the stock market because the initial yield is your best estimate of your long-term return in fixed income.

If you are a long-term investor who uses bonds in your portfolio, you should consider increasing rates. This is a good thing in the long run.

You just need a little patience in a short period of time to get there.

Further reading:

interest rates are getting weird