When Should You Sell a Stock That’s Down?

A reader asks:

Ben, you’ve shown time and again that owning the market is a better strategy than choosing different names; However, for those who enjoy the market and want to have some fun on Robinhood, what advice do you have for someone who has found themselves down 25% and 34% in their two biggest holdings and they live below average, but they can’ you ever get below? Historically, do most stocks bounce back from such declines, or does the data tell you to cut your losses, even if they are so painful?

This is something a lot of stock-pickers are dealing with at the moment.

Four out of every 10 stocks on the Nasdaq are currently down 50% or more from their 52-week highs. One out of every 5 stocks in the S&P 500 is down 20% or more from last year’s highs.

And that’s at a time when the S&P 500 itself is down less than 2% from an all-time high.

The first problem for many new stock-pickers is that it was too easy to come out of the corona crash. According to Jason Zweig, 96% of all stocks in the US stock market were up in the ensuing year, from the bottom on March 23, 2020. It was a record high and an outlier.

Most of the time, many stocks will be down even when the market is up.

Last year the S&P 500 was up nearly 30%, yet 13% of the stocks in the index were down in the year. In 2020, the S&P ended with a gain of more than 18%, yet a third of all stocks were in the red by year’s end.

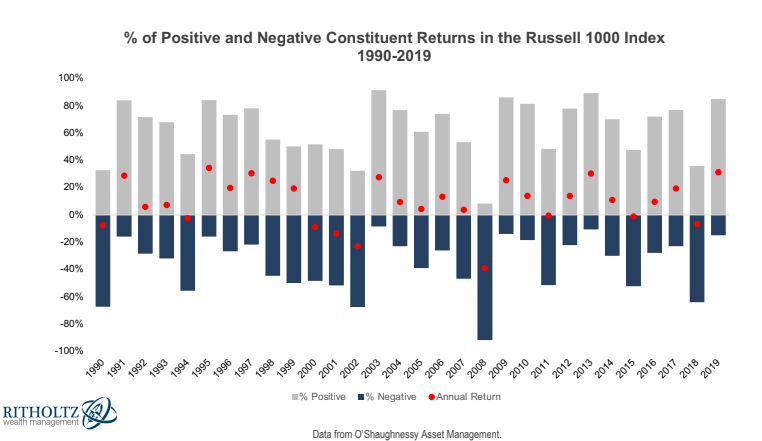

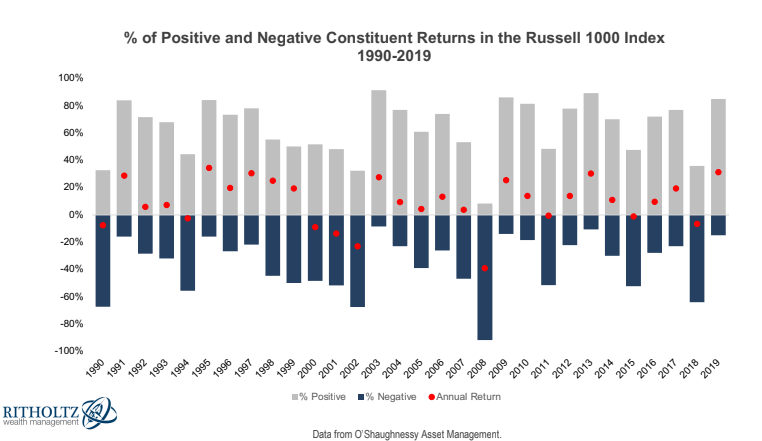

My friends at O’Shaughnessy Asset Management looked at the number of positive and negative returns on the Russell 1000 Index each year since 1990:

Every year there are a number of stocks that have losses, even in a year in which the overall market provides gains.

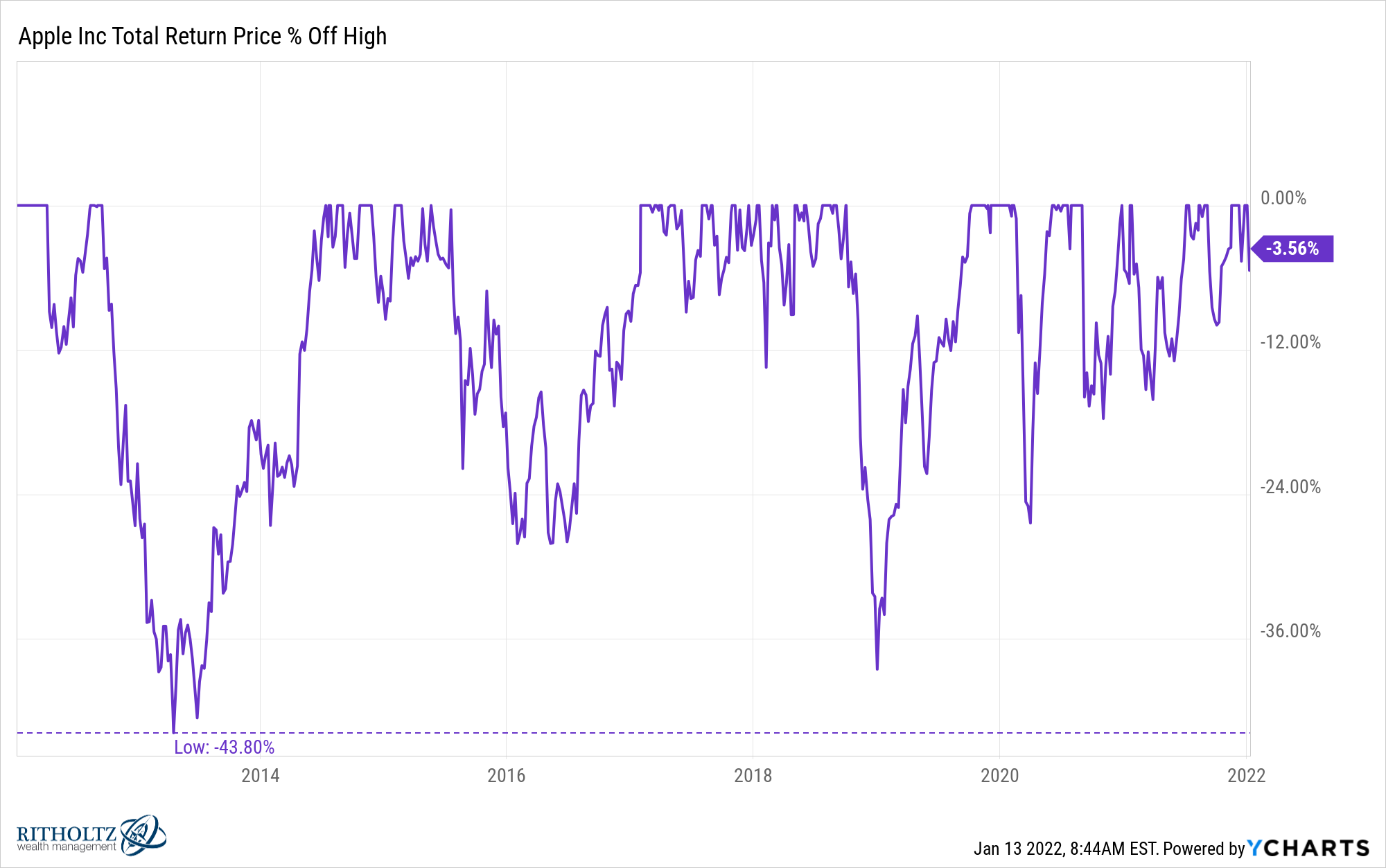

Even a company like Apple that has seen total returns in the neighborhood of 1200% over the past 10 years has experienced its fair share of drawdowns:

I count 7 separate double-digit drawdowns in this time frame, including 4 separate losses of 25% or more (the S&P 500 is down 25% or more over the past 10 years).

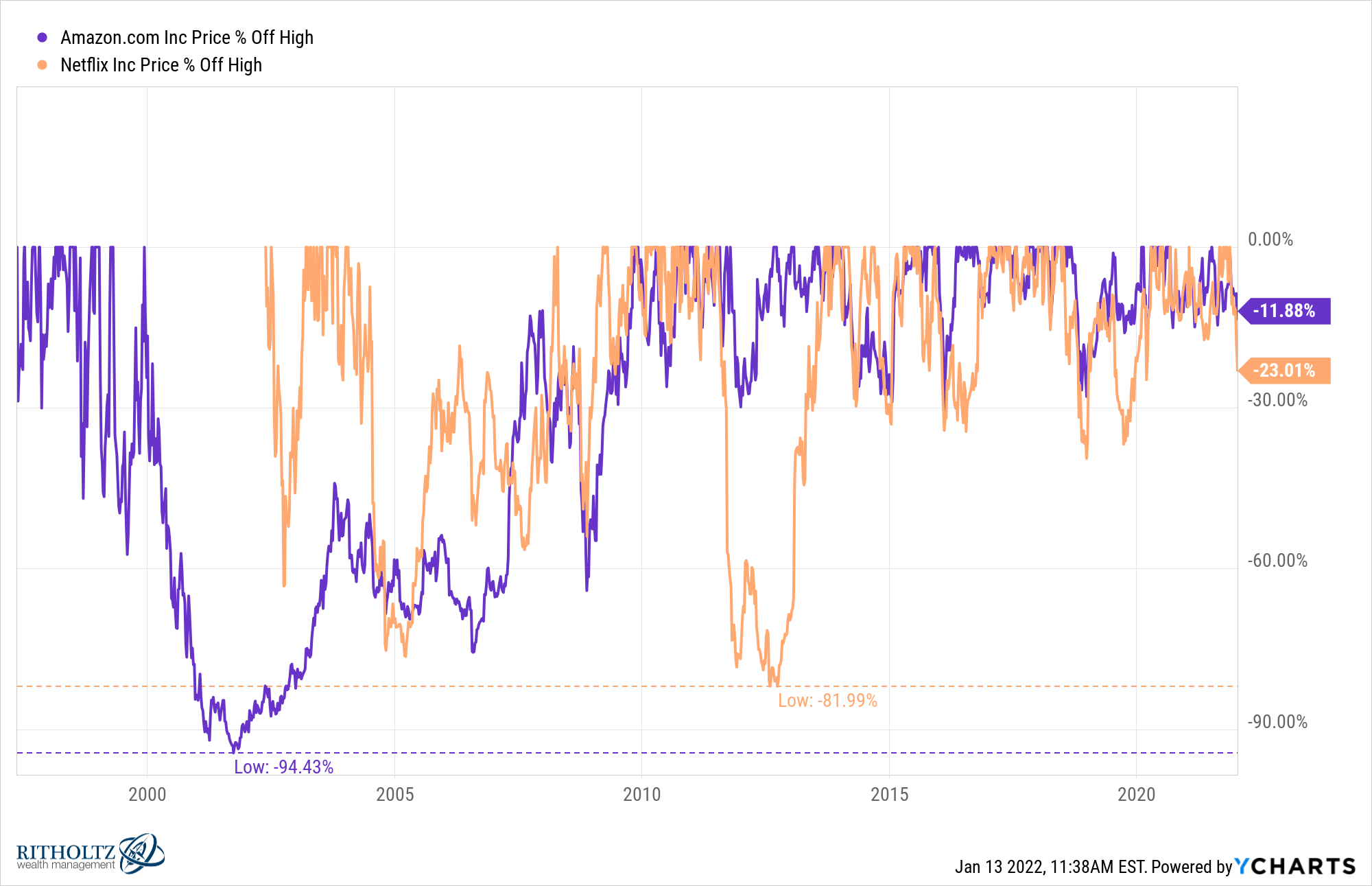

Even the best stocks go bad at times. Other examples include losses of 94% and 82% for Amazon and Netflix, two of the best-performing stocks this century:

Buying some of the best stocks in the midst of a massive downturn presents a great opportunity for investors.

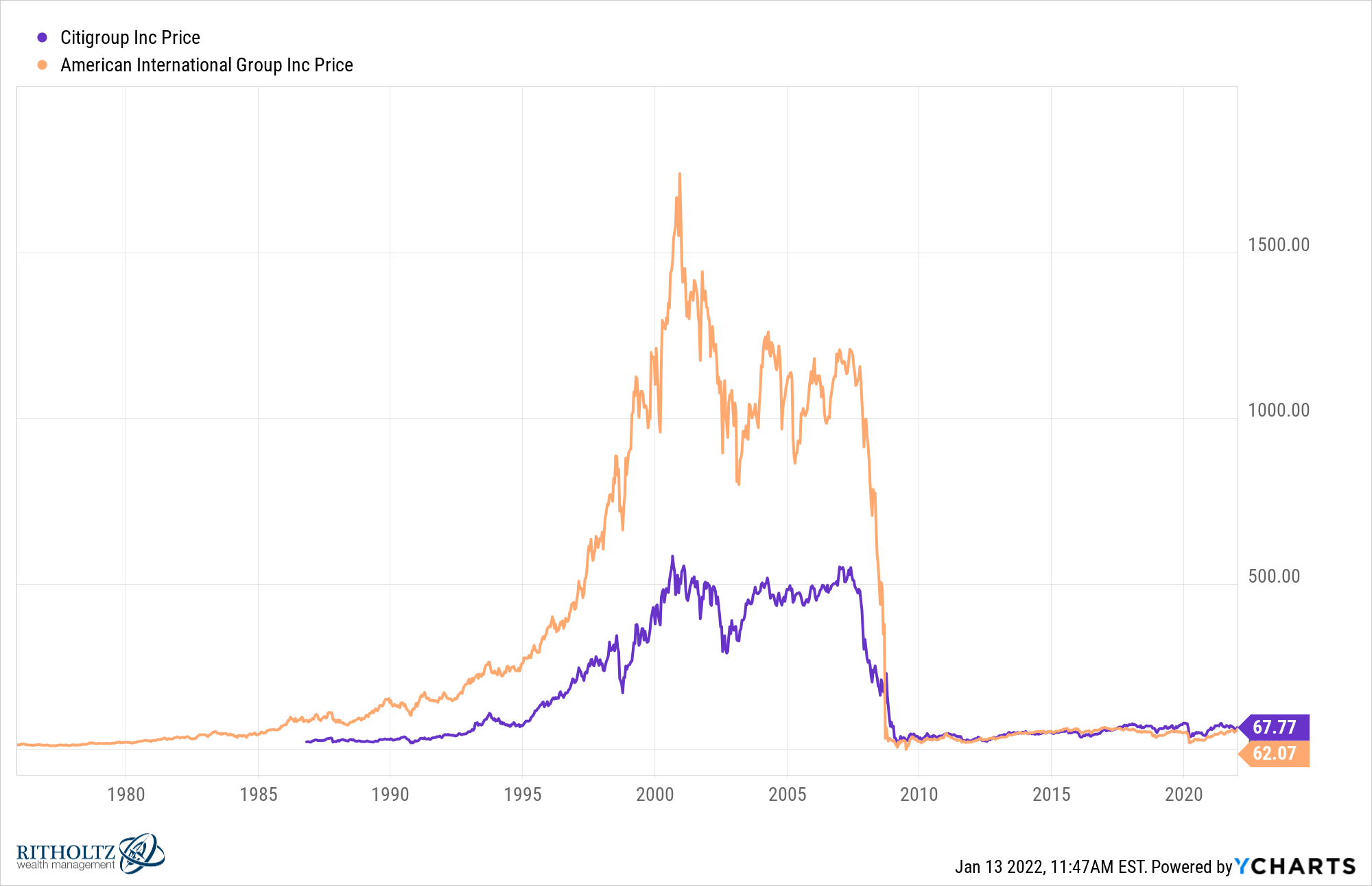

On the other hand, there are stocks like Citigroup and AIG that fell 90% and still haven’t recovered:

Of course, there’s a lot of room between AGI and Citi’s crushing low versus the peak highs of Apple, Amazon, and Netflix.

One of the reasons that owning the market through an index fund or another diversified ETF or mutual fund is a lot easier than owning individual stocks because you can eventually bank on average reversion.

No total market index fund is ever going to zero, so you may be more comfortable buying or rebalancing in pain when the market goes down.

This isn’t true when it comes to individual stocks, so it makes the idea of below average that much more difficult.

When the market is up and you have a stock that is down it can play the head game with you. The problem is that there are no fixed rules for when to sell to a loser.

There are lots of good books out there about when to buy stocks. You can use financial statement analysis, quantitative screens or technical analysis.

And if you’re a fundamental stock-picker, a quantity or technical analyst, you have at least a few terms and numbers you can refer to to guide your actions.

Most regular people buy what they know based on the products or services they use. People who dabble in stock-picking tend to buy brands, trends, stocks that are in the news or stock tips. This makes it very difficult to know when you should cut the bait and move on.

The hard part is that there is a fine line between discipline and madness when it comes to investing. If you still believe in the company then being a disciplined investor you will have to continue with the average decline. Taking things too far can mean throwing good money after bad.

It is impossible to know which stocks are going to come back stronger and which are going to stabilize because we cannot predict the future.

Since I can’t answer with certainty whether it makes sense to buy, hold, or sell more, here are some questions you can ask yourself when you consider what to do with your stocks that are rising from higher levels. have fallen:

- What is my threshold for personal name pain — 30%? 40% 50%? 60%? If you are a long-term investor, expect to cut your individual shares in half at least once.

- Am I thrilled to buy this stock at low prices? When a stock is higher than it is low it is very easy to answer this question but it can also help you set your risk profile.

- Has the story changed? You can’t answer this if you didn’t have a predetermined reason for making the purchase in the first place.

- Do I have better investment opportunities elsewhere? Every investment decision – buy, sell or hold – can be viewed through the lens of opportunity cost.

It is always easier to sell a stock when you have a profit. It’s more difficult to sell when your stock is down.

No one wants to look like an idiot for selling to the next big winner just because it’s in decline.

We talked about this question on this week’s Portfolio Hedge:

I also had Nick Magiulli to help me go over lump sum versus lump sum. Market dollar-cost averaging with bonus money, when to cut back on retirement savings and how to think about using leveraged ETFs in your portfolio.