the future is hard to predict

In April 2001, Lynn Wells of the Pentagon asked President George W. Bush with a subject line that read: Predicting the future. It was just one page long:

His conclusion was about as good a prediction as you can make about the future:

I’m not sure what 2010 will look like, but I’m sure it will be a lot less than we expect, so we should plan accordingly.

History is full of surprises. This letter was sent a few months before the 9/11 terrorist attacks. That decade also included the massive housing market crash and the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Since then we have experienced many wars in the Middle East, Brexit, trade wars, insurgency in the Capitol, pandemics and now a war in Ukraine. I could list dozens of other geopolitical events and crises in the meantime.

I’m a big fan of reading history as a way of helping me understand the present. Unfortunately, history can be a terrible teacher. There are no counterfactuals. It’s a lot easier to play quarterback on a Monday morning when you already know exactly what happened.

Making predictions about the future based on the past is like watching The Sixth Sense when you already know that Bruce Willis was dead the whole time.

The past is easy because it seems so clean while the future is difficult because it is messy. But even the explanation about the past is not as clear as it seems.

Philip Tetlock has spent his career tracking the forecasting abilities of experts. He once wrote about why it is so hard to learn from the past:

A warehouse of experimental evidence now testifies to our cognitive deficiencies: our willingness to jump the heuristic gun, being too fast to draw strong conclusions from ambiguous evidence, and too slow to change our minds because observations are difficult to confirm. Is. The balanced contribution of dosha must be acknowledged that Learning is difficult because even experienced professionals are incapable of dealing with the complexity, ambiguity and inconsistency inherent in assessing causality in history., There are many strange happenings in life that the thoughtful observer feels obliged to explain because the policy stakes are so high. Although, Just because we want clarification doesn’t mean someone is within reach, To achieve interpretive endings in history, observers must fill in missing counterfactual comparison scenarios with elaborate stories based on their deepest beliefs about the way the world worked.

I have written the following why history is always wrong,

People are constantly rewriting history for the simple fact that history is hard to define, even for those who have lived or studied it.

Abraham Lincoln has been the subject of nearly 40,000 (!) books.

The Battle of the Bulge took place about 75 years ago. At least 8 books were written on this one WWII war from 2014-2016.

World War I happened more than 100 years ago. There were a half-dozen books, each hundreds and hundreds of pages, published in 2014 alone, explaining why the Great War broke out in the first place.

Historians have given more than 200 hundred theories about the causes of the fall of the Roman Empire.

The Dutch tulip frenzy of the 17th century is considered by some to be one of the greatest bubbles in history. Others underestimate what happened and think that the whole incident was exaggerated.

The SEC wrote an 840-page report to explain the Black Monday crash of 1987. Investors still debate about what exactly caused the biggest one-day loss in stock market history.

Google gave me 374 million hits on ‘The Great Depression’ and experts still can’t fully explain why it happened the way it did.

If we have difficulty interpreting the past, what chance do we have of consistently predicting the future?

The world is a very different place now than it was a week ago. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has turned the geopolitical world on its head.

I have more questions than answers right now:

- What is Putin’s final game here?

- How is it possible to move forward with Putin under the leadership of Russia regardless of the outcome of the war?

- What will be the unintended consequences of the crash of the Russian economy?

- Will America and other developed countries go to war?

- What does this mean for the Fed and inflation?

- How will the stock market react to the ongoing war?

- Does Russia Experience Hyper Inflation?

- Does this make China more or less likely to invade Taiwan in the future?

- When will this struggle end?

I don’t know how you can more or less destroy an economy like Russia and not have unintended consequences. I don’t even know how you can have a war between two countries which have about 200 million people and when all is said and done things go back to normal.

I’m not going to pretend to know the answer to any of these questions right now. This situation is so complex and dynamic that it is impossible to predict how it will end. This is a situation where it is nearly impossible to constrain the possible outcomes.

All I can predict at this time is that things will get better in the long term, hopefully for both countries, as most people wake up in the morning and want to look better.

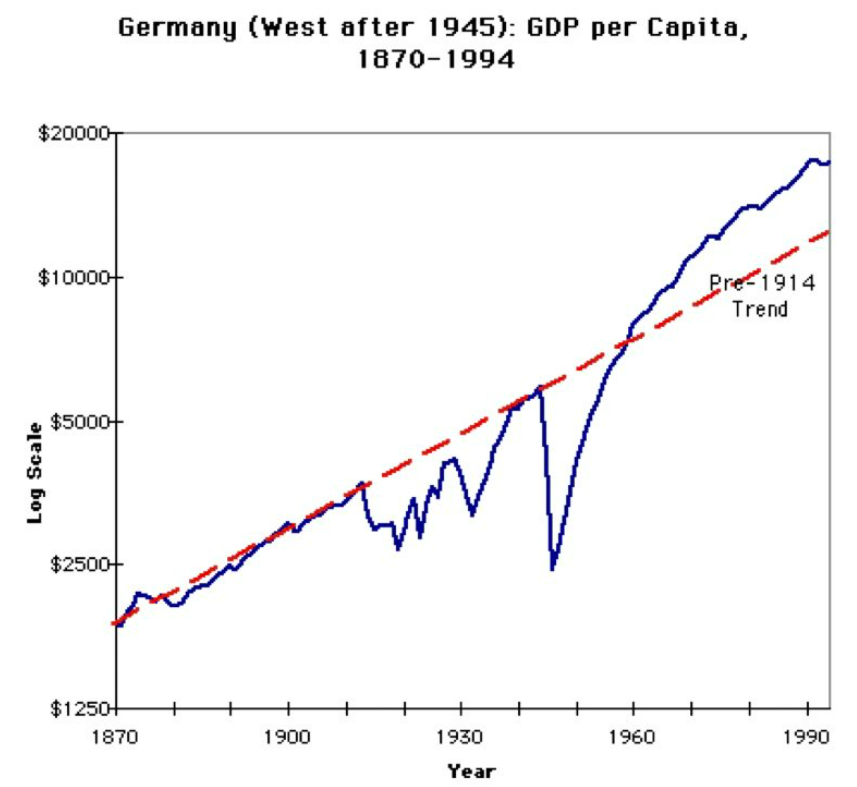

Speaking of post-war economic statistics, the per capita GDP I’ve ever seen in Germany after WWI and WWII is:

Germany experienced hyperinflation after World War I and saw its economy collapse after World War II. Yet they had the fastest growing economy in all of Europe since WWII. They were in trend back in 1960.

There are differences of opinion as to how the rest of the world handled after each war, but I’m not sure anyone would have predicted this after seeing what happened to the German economy after WWI.

It is difficult to see an easy way out of the current geopolitical nightmare in the short term.

It is always a bad idea to bet against the power of the human spirit in the long run.

Further reading:

why history is always wrong